A Brief Introduction to Vibrato Experiment 212b

Not a lot of people know this but there’s actually a reason why so many professional musicians instinctively discourage the extended use of vibrato. A good reason.

We all know the standard line, the received wisdom: It is only the middling singer who utilizes an exaggerated vibrato of, say, nearly a semitone (known in the business as “wigglin’ the pitch center”) to disguise, via a sort of law of aural averages, their incapability of producing a clear, on-pitch, pure note (e.g., your ear hears the note wagglin’ so hard that it, your ear, supplies the “correct” note, much like staring directly at the sun and then immediately immersing yourself in the darkness of an underground cave will produce a pleasant muted gray in your eyes). Many vocal coaches deride this as a crutch.

But the real reason why they are uncomfortable with such profligate wobbling is far darker and stranger. They can sense it, somewhere deep below thought.

Recent studies[1] have shown that when a human singer produces a very wide vibrato at exactly 99 cents above and below the fundamental tone, odd things begin to happen. And precision is key here: The pitch must waver at exactly ±99 cents (just shy of a semitone/half-step in both directions) for several minutes, a feat that’s all but impossible for even a professional vocalist with the hypersexual beard of a Pavarotti. And even a single singer isn’t enough to produce the full Effect; three (3) are required, each of them with perfect pitch and a nearly inhuman control of their larynx.

When Singer A performs the 99-cent vibrato (starting from, say, an A-natural at 440 Hz and rising to 1 cent shy of B-flat and falling to 1 cent above G-sharp)[2] for at least 180 seconds steadily, observers note an odd ringing in the ears, just perceptible below the tone, and sensors placed around the room report a rapid temperature decrease of 3.5 degrees Fahrenheit. The sensors are checked and rechecked. The readings are correct.

When a second vocalist, Singer B, steps up, sucks in a huge blue lungful of air, and begins their own 99-cent vibrato exactly a semitone above Singer A (e.g., starting from a fundamental of B-flat), again for 180 seconds, observers begin to report a shimmering black light at the edges of their vision. The temperature begins to decrease and increase by, again, 3.5 degrees, both above and below the original room temperature, at a rate mirroring the rate of vibrato.[3]

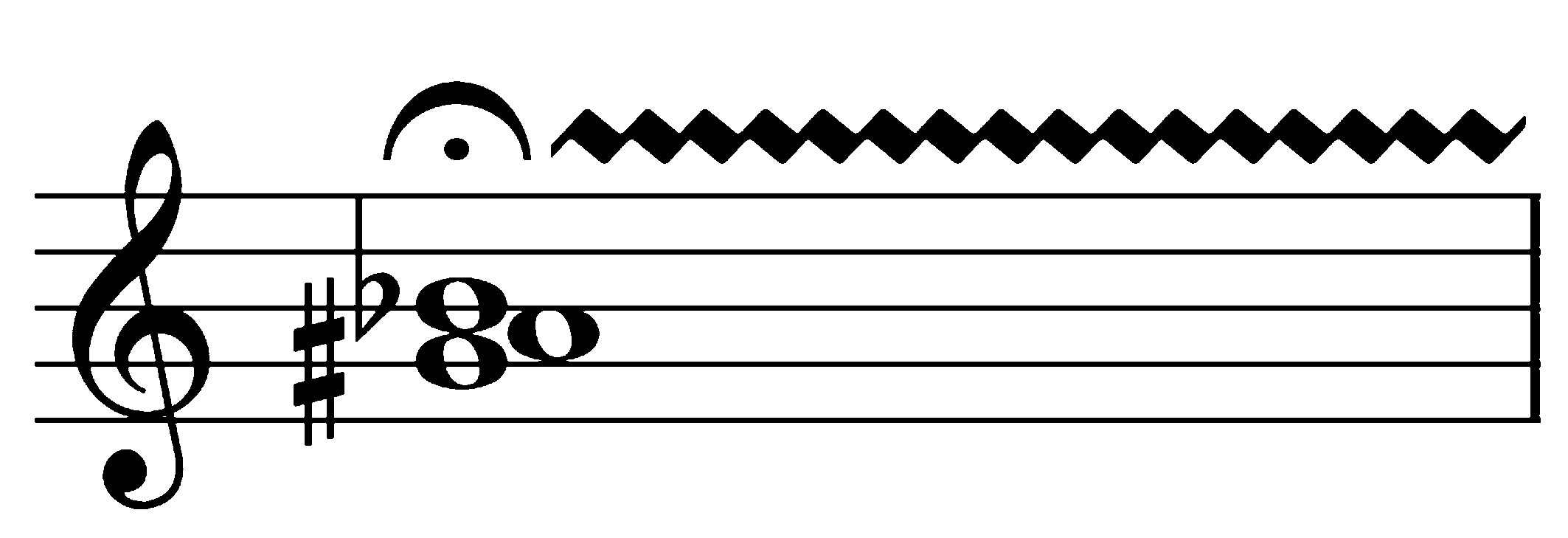

But it’s when Singer C is introduced to the mix that the full Effect is at last produced. This third vocalist must begin their 99-cent vibrato a semitone below the original Singer A (e.g., starting at G-sharp). All three singers must therefore have their pitches clustered in a perfect three-semitone “chord” (which may, we understand, sound somewhat dissonant to your ears, if you’re a fool and a baby), the three notes rising and falling at exactly the same rate (see notation below).[4]

When Singers A, B, and C, positioned at the vertices of a perfectly equilateral triangle and each facing the center of said triangle, perform this mathematically exact feat for a full 180 seconds, we begin to see the Effect. And we here at Excessive Vibrato are the first in modern history to observe and document it—though of course ancient texts seem to indicate the Effect was at least partly understood among certain cultures in antiquity.[5]

The Effect: In the center of the triangle, a rough shape appears, dark and gleaming. It swims out of focus; it is difficult to perceive when observers look at it directly; it is clearer in your peripheral vision when you look at a point several feet to one side. Eventually it becomes spherelike,[6] its surface rippling. The orb hovers and rotates in place. It is small, roughly the size of a large candy jawbreaker or a bull testicle. And it emits signals, radio-wave frequencies.

Our batteries of specially designed antennae receive and translate these frequencies. Curiously, the signals appear to be transmissions from an Alternate Place (AP), or perhaps from multiple APs. The signals appear to be accidental rather than intentionally sent to us here. We are receiving the runoff from elsewhere, in runnels and rivulets.

Most of the pieces we’ve received thus far seem to be electronic messages posted on an analogue of our own internet, or “computerweb.” The APs they originate from seem superficially similar to our own, yet oddly off-kilter.

All the pieces presented in this newsletter have been collected from those transmissions and reproduced exactly as discovered, occasionally with gaps and lacunae.

Unfortunately, we have thus far been unable to pass any solid objects into the orb. We originally planned to continue our experiments indefinitely, but one of our Singers (Singer B) developed bronchitis and needed to be hospitalized, like a weak little Victorian child. And another (Singer C) grew uncomfortable with our approach and requested to leave the trial, severing her contract early. The coward.

We are on the hunt for replacements, but it’s not easy to find a single vocalist with that level of computer-perfect control, let alone two. Please contact us if you know anyone.

We will continue to post the transmissions we previously received from the AP(s) until we run out.

Thank you.

See Sixsmith, “Quantum and Quasi-Quantum Effects in Rapid Vocal Pitch Modulation,” Journal of Esoteric Musicology, Winter 2023, and Gerber et al., “The Snake in the Song: Laryngeal Temperature Fluctuations in Exaggerated Vocal Vibrato,” Experimental Acoustics, June 2024. ↩︎

For illustration purposes only. The specific starting pitch doesn’t seem to matter; even microtonal starting pitches will produce the Effect as long as precision is observed elsewhere (e.g., rising and falling ±99 cents from a base of C-half-sharp is just as effective). ↩︎

The specific rate/speed of vibrato also doesn’t seem to alter the Effect, as long as the pitch varies a minimum of 4 times per second. Note, however, that the rate of vibrato must remain constant to produce the Effect. ↩︎

To forestall the inevitable questions from our many doubters and haters: No, computers and keyboards and synthesizers cannot produce the Effect, no matter how exact their pitches. Nothing artificial works, and even acoustic musical instruments fail to produce the Effect. The Effect seems to depend somehow on the unique resonance of the human voice. ↩︎

See Mordent and Calvino, Pythagorean Chant and the Priestly Caste, p. 186ff. ↩︎

Why a sphere? Consider this thought experiment: If we lived in a universe whose dimensions were n–1 relative to our own, spacetime would be a flat, two-dimensional plane. Imagine it as a sheet of plain paper. Now draw two points on the paper, at opposite ends, and label them A and B. Normally, the shortest distance between points A and B would be a straight line, and you’d need to travel across the entire plane to traverse that distance. But if you could fold the paper so that points A and B were directly atop each other, and then you punched a circular hole in the paper where both points lined up, you could travel between them much more quickly, or at least send information between them. Now extend this to three dimensions instead of two. If the plane were a 3-D hyperplane and you could somehow “fold” the hyperplane, then the “hole” connecting A and B would be a sphere rather than a circle. ↩︎