Advanced Jazz Chords for Sick-Ass Bosses Who Don’t Play by the Rules

There are those for whom the complexities of music theory seem needlessly mathematical, even esoteric—the soulless reduction of a wriggling, living art form into frigid lines and numbers in some dusty book.

Then there are the others, the hardcore nasty captains who know better, such as yourself. Who cut their own meat and guzzle life like a frosty pint of Everclear. I can see that you’ve come here for the good shit, the raw gnarly sap gushing out of the tree, so let’s get right to it.

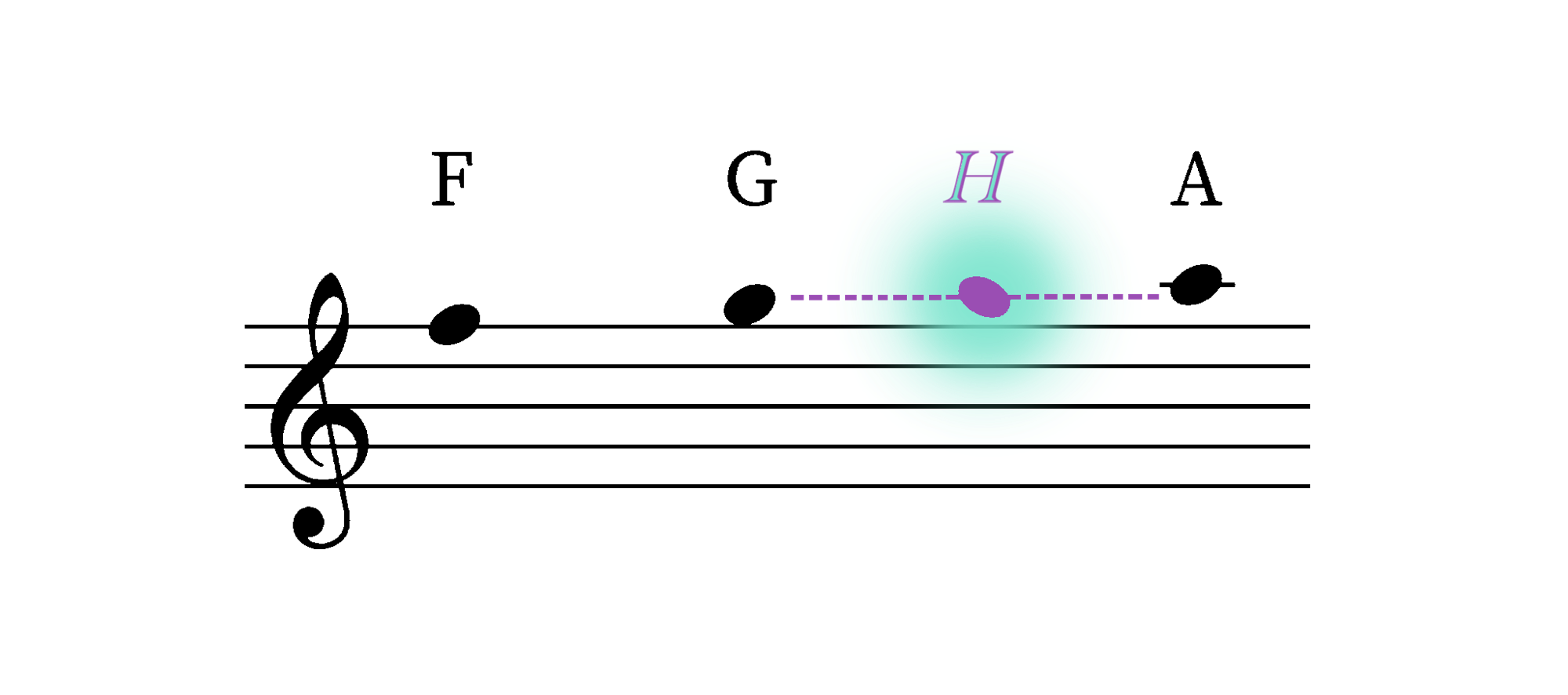

Hmaj7

In the dim hinterland between G and A lies a secret note, accessible only via the dark practice of Negative Tuning or, in a pinch, interdimensional folding.

Once you’ve found the elusive H-natural note, proceed as follows: Construct a major-seventh chord around the H by adding the third (J-natural), the fifth (L-natural), and the major seventh (N-sharp), and you’ll get the surprisingly ominous-sounding H-major-seventh. Use sparingly; it has been known to cause spontaneous and irreversible tinnitus.

Note: Some theorize that Hmaj7 is the “secret chord” that Leonard Cohen described King David discovering in antiquity and using to tickle the fancy of the Almighty. Unproven—all of David’s recordings have been lost—but intriguing nonetheless.

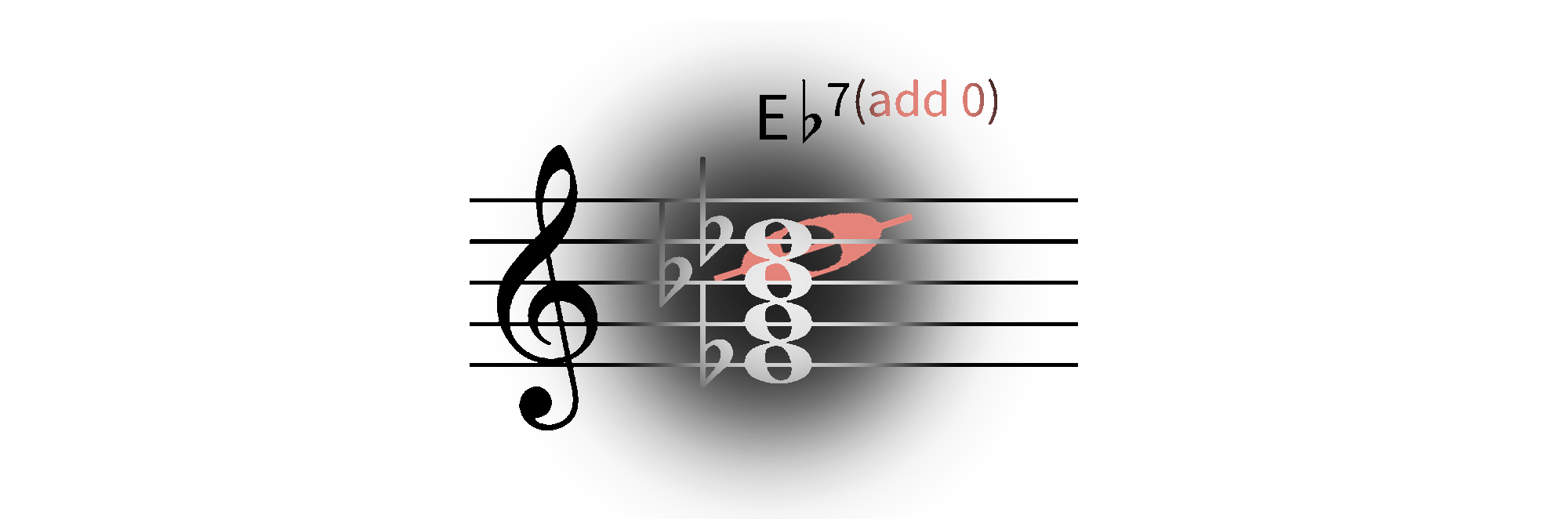

E♭7(add 0)

Add subtlety and spice to your arsenal of dominant chords by playing an E-flat-7 with the zesty inclusion of the zeroth scale degree. Simply take your tonic (E-flat, the “one”) and go down by one. No, not to D; that’s the seventh. Go deeper. Go downer. Unfocus your eyes and cast off the heavy dinner jacket of the physical world. Look harder; you’ll find it.

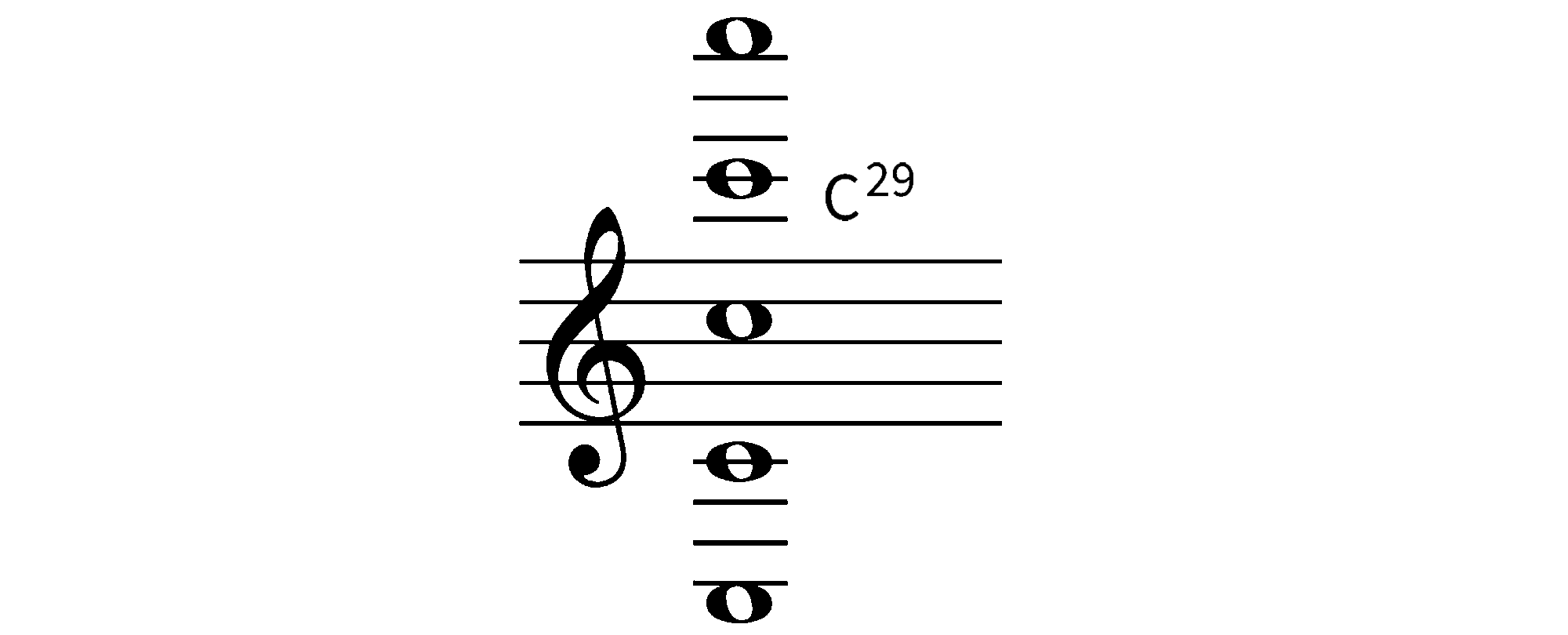

C29

Simple as they come. Take your root note (C) and stack atop it an eighth (counting eight up from C, that’s C). On top of that, add the 15th (counting carefully up from the eighth of C, that gets us to C). Then—and here’s where things get tasty—add the 22nd (also C). Make that gnarly chord really sing with one final extension: the 29th (C again). Quite the reach on a piano or guitar, but you’ve got this.

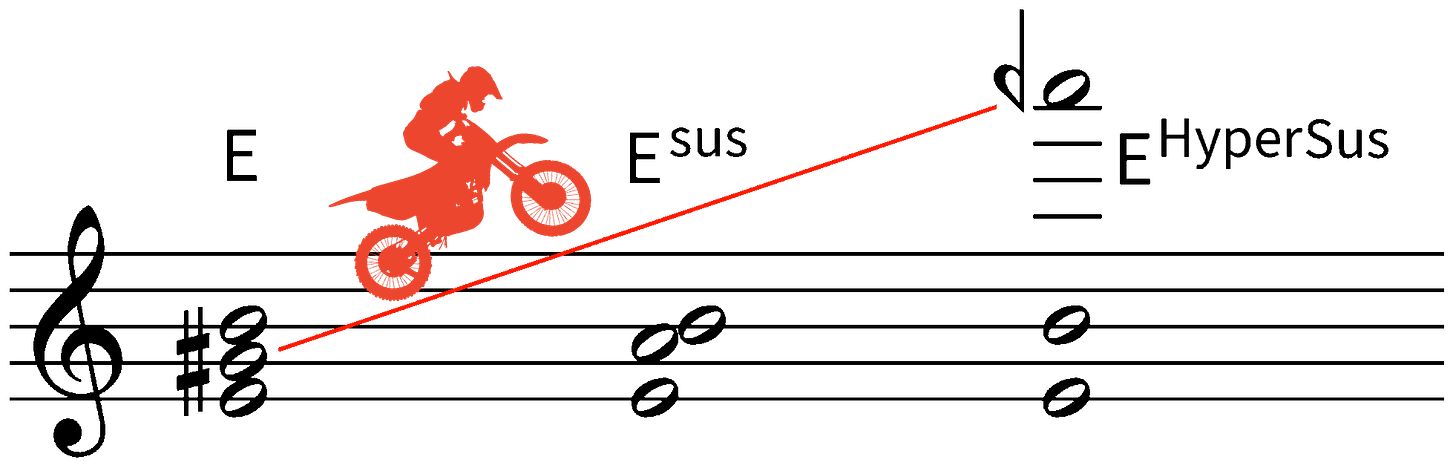

E(HyperSus)

Suspended chords are a nice way to add small amounts of tension—FOR BABIES. Grow the fuck up, dude. Ditch the childish suspended fourth and take a ride on the HyperSuspended, the sick hog of chords. Unlike a regular suspended chord where you replace the third with the fourth (e.g., E, A, B) and then resolve it by returning to the standard major triad (e.g., E, G#, B), an E-HyperSus involves taking the third and raising it to a trembling quarter-flat 18th. And don’t you dare resolve it. We’re fucking adults here.

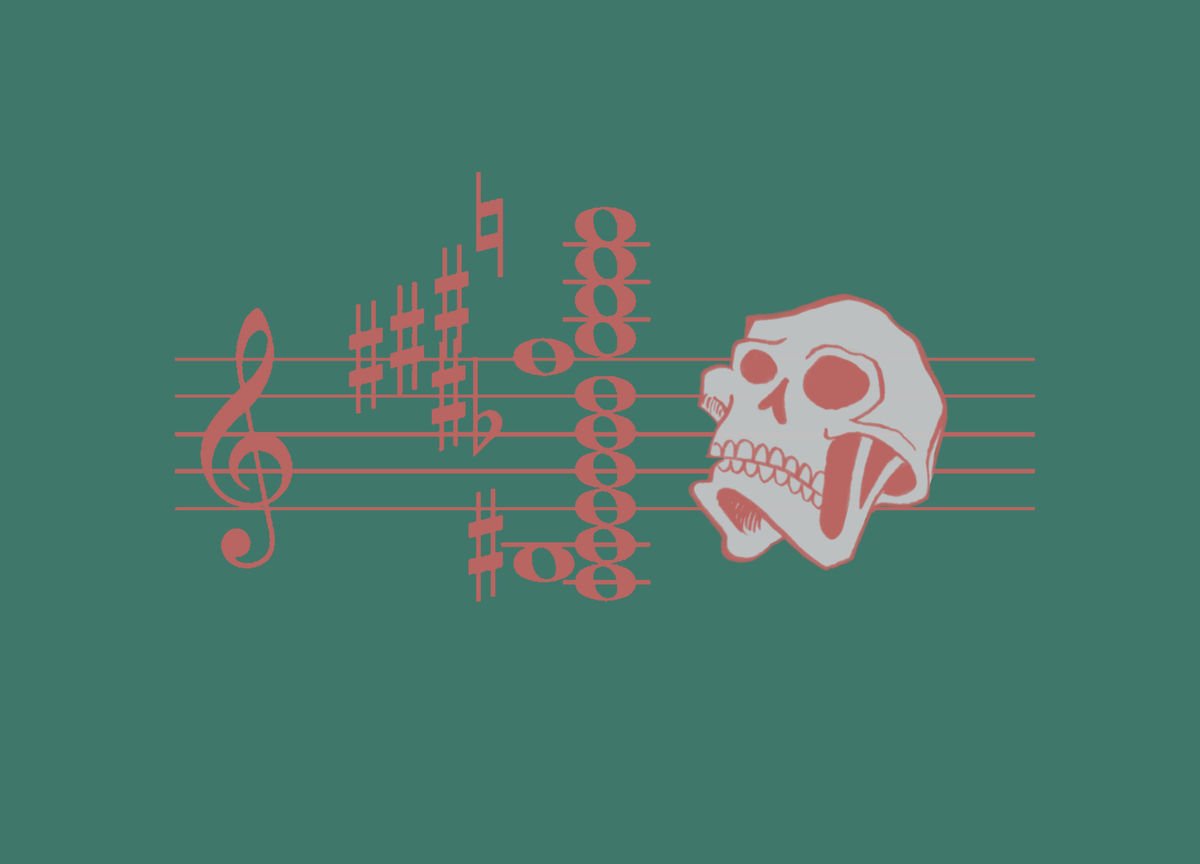

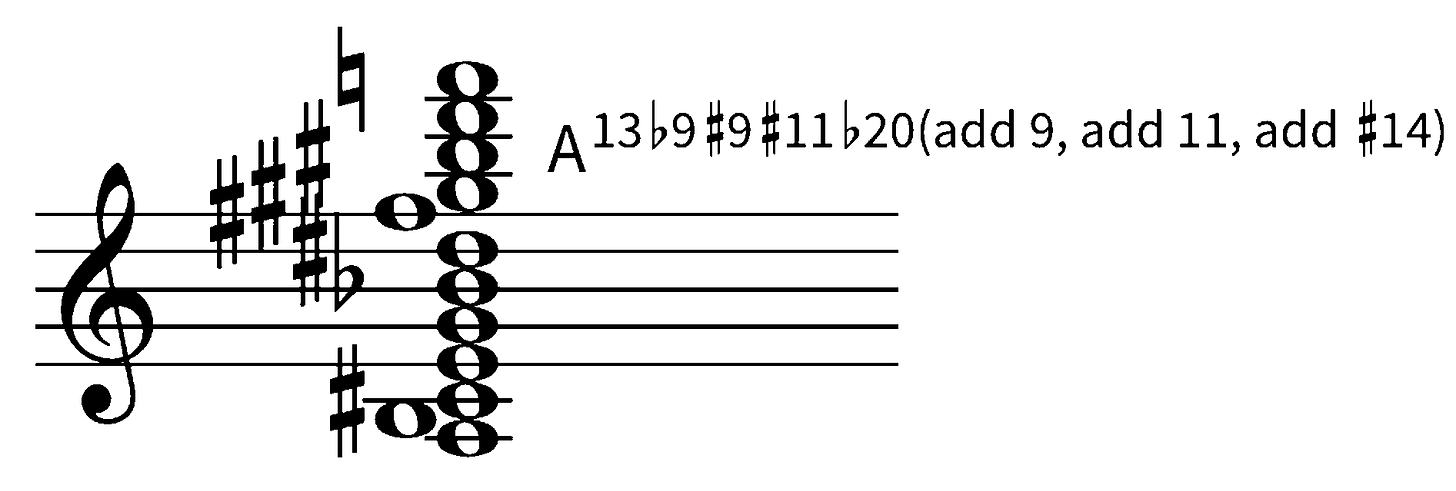

A13♭9#9#11♭20(add 9, add 11, add #14)

Really wow ’em with this tasty little piece, the A-thirteen-flat-nine-sharp-nine-sharp-eleven-flat-twenty-add-nine-add-eleven-add-sharp-fourteen. Simply take your classic A-dominant-7 chord and add a few shimmery little jazz extensions until you’ve covered all 12 notes in the chromatic scale (aka “the sex-haver’s dozen”). You’ll be fending off wildly attractive demigods with a stick! I heard this chord at a club once and it made me bleed from my ears.

Cm(#3)

Unexpected yet refreshing, like waking up abruptly to someone dumping a gallon of ice-cold Sprite into your mouth, this bad boy is formed by first taking a classic minor chord (root, minor third, fifth) and then delicately raising the third by a half-step. The minorness of the chord is thus sublimated into something more elegant and transcendent, something almost mystical. The inherent darkness of the minor is lifted into a sticky-sweet caramelization that seems at once airy and ponderous.

The crude and the crass may claim that this stunning new development in the chordal arts is identical to a simple major triad (root, major third, fifth), but that’s because they’re the sort of people who vacation in Sacramento and think the table shaker of pre-ground black pepper is a little too spicy. “Identical”? That’s like saying Pierre Menard’s Quixote is “identical” to the Cervantes original. It’s called classiness—look it up.

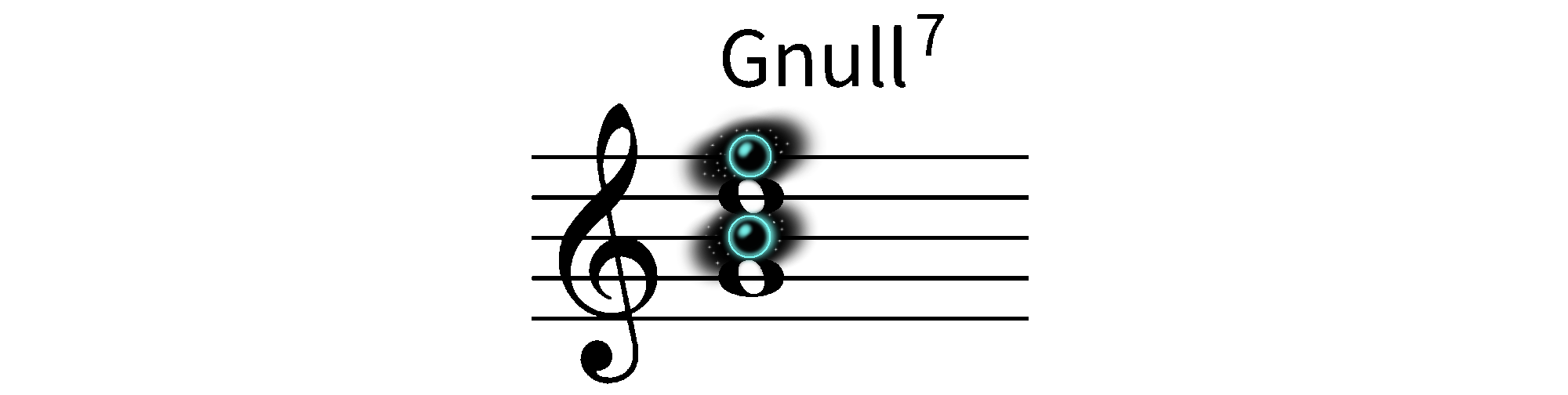

Gnull7

When your solos are getting a little dull and your chord progressions elicit stifled yawns from even the heavily goateed bruiser at the back of the room, it’s time to reach for the Gnull7. “But please, how do I form the Gnull7?” The first step is admitting your ignorance, which you have just done. Bravo. The second step is to take a minor-seven chord—in this case, Gm7—and nullify both the seventh and the third, leaving you with twin auditory chasms that will impress upon the listener a kind of alive, buzzing emptiness. It’ll knock his stupid goatee right off his assing face.

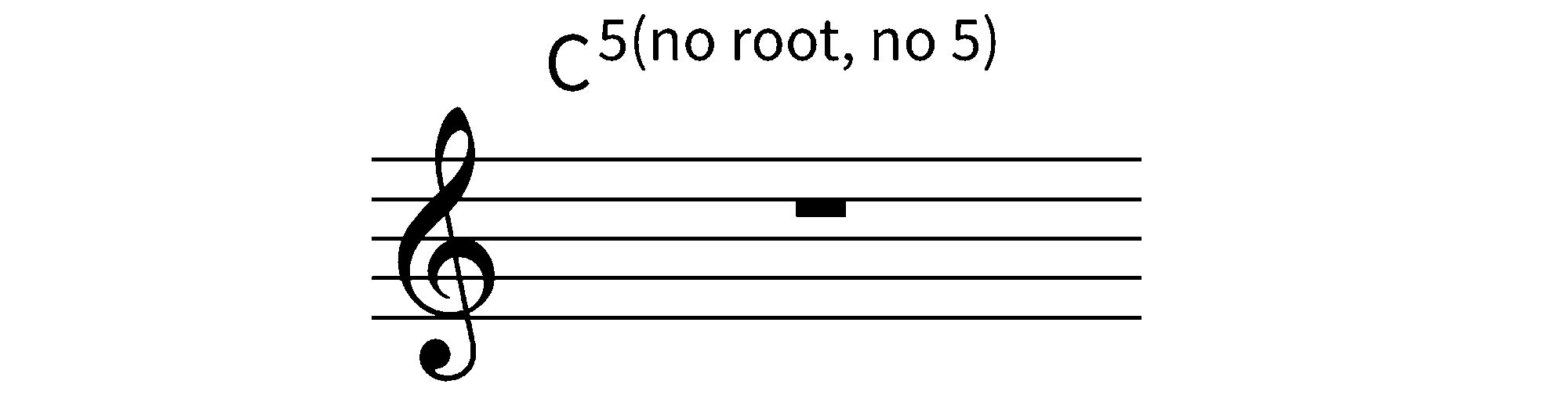

C5(no root, no 5)

The so-called “five chord,” aka the “power chord” beloved by middling guitarists everywhere, consists of merely the root and the fifth, with optional repeated root an octave up. Lend your power chords a bit of zing, a bit of oomph, by omitting the root and the fifth entirely to get the cutting-edge C5(no root, no 5), only recently discovered by musicologists. The rootlessness lends an air of uncertainty, a soft-as-dragonfly-wings musical question mark, while the fifthlessness catapults the chord into the etheric upper airs of true artistry.

B(nasty)

The chordal version of pure, undiluted sex, like Elvis’ heaving neck. I can’t tell you how to play it. IYKYK, and IYMFKYMFK. You’ve either got the juice, or you haven’t.

D(blue)

You might be thinking, “There’s major, and there’s minor. The two are distinct, and this is an inviolable law of the universe.”

You fool. You simple country rodent. You unsauced bowl of spaghetti and meat balls.

If you can attempt to use your atrophied imagination for one goddamn second, envisage the Western musical scale as a slide rather than a staircase. There are infinitely many notes between each note. Each half-step can be further divided into quarter-steps, eighth-steps, and so on, Zeno-style, as evidenced by the very existence of a smooth glissando on a trombone. Go ahead and find the aural spot precisely halfway between a minor third and a major third, and what do you get? The fabled “blue” note of jazz, neither major nor minor, or perhaps both at once. Now then, starting on a sturdy, respectable D-natural, build a triad with this blue interval (root, blue third, fifth [D, F-half-sharp, A]). Don’t be afraid. Sauce yourself now—quickly. Welcome to the new world.

𝛡-major, 𝞇-minor, ᛪ-diminished

The three so-called “unspeakable chords” spoken of in 2 Corinthians 12:4. Use with caution, as they are, in some traditions, considered the triple pillars that hold aloft the Godhead Itself.